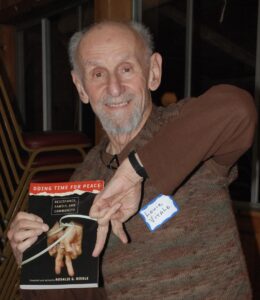

Louis John Vitale.

This Franciscan friar, advocate for peace and justice and nuclear resister died on September 6, 2023 at age 91.

A man of kindness and love and gentle strength, with his heart and faith and conscience always leading the way.

from Pace e Bene

Nonviolence in Action: Remembering Louie Vitale

by Ken Butigan

September 6, 2023

In 2012, Louie Vitale received an honorary doctorate from the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. The building was packed with students and their families. The highlight of the event was the conferral of three honorary doctorates. Two scholarly gentlemen collected their award and delivered magisterial exhortations brimming with scholarly exegesis. Then it was Louie’s turn. His presentation was short and to the point.

“I’ve discovered in my life,” he said, “that love is what matters in the end. And all I can say is: I love you! I love you! I love you! I love you!” And then, with a final, rousing “I love you!” as he waved his arms in a vigorous gesture of blessing, he sat down.

The crowd broke out in long and delighted applause.

Friar Louie Vitale, OFM—a Franciscan priest, past provincial of the St. Barbara Province of the Franciscan order, co-founder of the Nevada Desert Experience, which worked with other organizations to successfully end U.S. nuclear weapons testing, founder of the Gubbio Project, which opened his church in San Francisco to the unhoused, co-founder of Pace e Bene Nonviolence Service, and an enduring exemplum of the nonviolent life—died in Oakland, Calif. on Wednesday, September 6. He was 91.

Louie’s longtime colleague and friend, Anne Symens-Bucher, accompanied him in those final days at the Mercy Center, his home for the past five years. Sitting at his bedside she stitched together Louie’s far-flung friends by text and invited us to join her in saying the rosary as Louie lay nearby. It was a great gift to be able, by Face-Time, to quietly share our love for this great apostle of love. Like the graduation audience in Chicago, we had all experienced his rousing “I love you” in words and deeds for many decade.

Via Face-Time, I shared my love for him from Chicago, and also my conviction that, in his coming new life, he would be met exuberantly by Saint Francis of Assisi.

But for the rest of us, we did not have to wait. We met Saint Francis in the life of Louie Vitale.

He embodied in our time so many of the 13th century saint’s facets of holiness: an abiding hunger for peace, justice for the poor and excluded, love of nature, and the longing to draw close to the presence of God, including through a contemplative life lived in the midst of the chaos of society.

Louie was a nonviolent change-maker actively immersed in one peace movement after another, challenging his government’s wars in Vietnam, Central America, Iraq, Afghanistan and many other parts of the world. He spent long stints in prison for nonviolent resistance to torture and war-making. For thirteen years he was the pastor of St. Boniface Catholic Church in a low-income neighborhood in San Francisco, where he was actively involved with Religious Witness with Homeless People, an interfaith campaign challenging poverty and government policies of harassment against poor and homeless people. All of this and much more found its way into a graduate course entitled “Liberating Nonviolence” we team-taught a dozen times at the Franciscan School of Theology, mentoring the next generation of peacemakers.

The Journey

Louie grew up in Pasadena, California. After attending military school he joined the United States Air Force in 1958, where, as a captain, he became a pilot and navigator on nuclear-capable jets. His father, Louis Vitale, Sr., had long expected his only son to follow him into the management of a highly successful seafood company that he had started in Los Angeles after arriving as an immigrant from Sicily as a young man. He was stunned and perplexed when his son announced, after finishing his tour of duty with the military, that he had decided to become a Franciscan.

Louie Vitale was enthralled with the life and work of Francis of Assisi. The son of a wealthy merchant, Francis grew up steeped in the vision of chivalric honor and romantic love. He went off to combat in a war between Assisi and a neighboring city-state. During one of the battles he was captured and spent a year as a prisoner of war. After being ransomed by his father, he underwent a profound conversion experience. In 1208 Francis took radically to heart the thoroughgoing demand of Matthew 19:21—Jesus’ call to the rich young man to give everything away and follow him. Francis, burning with the desire to imitate the poor and crucified Jesus, renounced his claims to his family’s wealth and espoused “Lady Poverty” or “Holy Poverty” as his lifelong companion.

Like Francis centuries before, Louie had observed the implements and dynamics of war at close range. Vitale did not serve in a hot war – his stint in the air force took place between the Korean and Vietnam conflicts – but he was actively enlisted in the Cold War struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union. Although he felt the allure of Air Force fighter jets, Vitale nevertheless began to question the projection of U.S. power they represented. He also worried about the threat they posed. Once as he and his crew were flying a routine mission along the U.S.-Canadian border, they received orders to shoot down an approaching aircraft determined by headquarters to be a Russian military jet crossing into U.S. airspace. Vitale radioed his base three times for confirmation, and each time the order was reiterated. Finally, the crew decided to make a visual inspection. When they did, they saw an elderly, smiling woman waving to them. At the last moment they averted shooting down a commercial airliner. This incident contributed to growing qualms about remaining in the military. In contrast to the life of a jet pilot, he felt increasingly drawn to religious life.

The roiling social conflict of the 1960s – and the nonviolent social movements that were active then – became a kind of formation process for Louie. In the 1960s and 1970s, he had worked actively on a number of social justice and peace fronts in addition to his anti-war and farm worker ministries, including solidarity work with welfare recipients and helping to found the U.S. Catholic Conference’s Campaign for Human Development.

Louie founded and served on the staff of the Las Vegas Franciscan Center in 1970 after completing a doctorate in sociology at the University of California at Los Angeles. He became the pastor of St. James Catholic Church, a parish in a low-income neighborhood on the west side of Las Vegas.

Louie had been elected vice-provincial at the end of the 1970s by members of his province— a jurisdiction that embraces much of the western United States—and was abruptly elevated to superior of the province when Provincial Minister Fr. John Vaughn, OFM was called without warning to Rome to lead the worldwide community of Franciscan men as the Minister-General of the Friars Minor of St. Francis of Assisi.

Through his active participation in the United Farm Workers’ struggle for the rights of the migrant poor and his visible opposition to the Vietnam War, Vitale was regarded as an emphatic advocate for justice and peace. In the wake of the heady days of the Second Vatican Council, Vitale was seized by the conviction that the work for peace and justice was central to the identity of Christians. This in itself was not unique. In the wake of Vatican II a growing number of Catholic clergy, women religious, and laity drew a similar conclusion and began to transform an insular church that had often supported social structures that reinforced injustice and war into a community prophetically seeking change.

What set Vitale and a relative handful of others apart were not their theological conversion but how they put it into practice. In his case, he marched and fasted with Cesar Chavez, vocally and dramatically decried the U.S. war in Vietnam, and publicly counseled and stood with young men who burned their draft cards and defied conscription into the U.S. armed forces. He supported the nonviolent civil disobedience of Daniel and Phillip Berrigan and lent his support to a wide variety of other nonviolent social struggles. Fr. Vitale’s years in Las Vegas motivated him to work with others to launch the Nevada Desert Experience, a faith-based movement to end nuclear testing at the nearby Nevada Test Site and to co-found Pace e Bene.

Perhaps my favorite writing of Louie’s was the series of prison letters he sent us when, in his 70s, he began to undertake a series of longer jail stints, usually about six months each, protesting torture.

At the end of a letter sent during a 2008 jail sentence, he wrote:

The cell door clangs shut. Now I am alone. But instead of trying to escape this solitude, I enter it deeply: This is where I am. Here in this empty cell I have begun to experience prison in the way James W. Douglass in Resistance and Contemplation describes it: not as “an interlude in a white middle class existence, but as a stage of the way redefining the nature of my life.” I have sensed this transformation, little by little. These days are a journey into a new freedom and a slow transformation of being and identity: an invitation to enter one’s truest self, and to follow the road of prayer and nonviolent witness wherever it will lead.

I am in this little hermitage in the presence of God, in the presence of the Christ who gave his life for the healing and well-being of all. I am also in the presence of the vast cloud of witnesses, some of whom are represented in the icons that have multiplied in this cell, gifts sent to me from people everywhere: Oscar Romero, Martin Luther King, Jr., Dorothy Day, Steven Biko, the martyrs of El Salvador, John XXIII. All those who have given their lives to fashion a more human world. At the same time I experience a deep connection with my fellow prisoners and with those outside these prison walls, including those who have sent me many letters and expressions of prayer and support.

In my little, empty cell, I experience a growing awareness of the communion of saints — and of the possibility of a world where the vast chasm of violence and injustice enforced by torture and war is bridged and transformed.

Simply powerful. And true.

Through all of this Louie brought a down-to-earth humanity. We talk about nonviolence being “love in action.” If this is the case, Louie was my great nonviolence teacher. For him, it was not just at a graduation ceremony where he declared, “I love you.” It was virtually every moment of every day.

And all with grace. And joy.

He could be anxious. He once told me his parents thought he was an anxious kid, and he never entirely shook it. But there was also a kind of ease with which he did his biggest things—heading off to jail for six months, traveling to Iran on a people-to-people peace mission, heading up one social justice campaign, and then another, and then another—because he knew who he was and what he was here to do.

It was a great gift to learn something about all of this from Louie.

* * *

In 2003 I published Pilgrimage Through a Burning World, a book that recounted the Nevada Desert Experience’s campaign to end nuclear weapons testing. A lot of this book is about Louie, even though he was not particularly good at organizing. There were many other great organizers involved, including Anne Symens-Bucher. Louie, instead, was more the movement’s catalyst and, ultimately, its soul.

The anti-nuclear testing campaign was just one of many, many efforts Louie was part of for justice, peace, and well-being for all. Many other vignettes could be posted from many different angles of Louie’s life. But below are some that shed some light on the inimitable Louie Vitale.

Thank you, Louie, for everything.

Ken

In 1981 Louis Vitale received a letter from the Minister-General in Rome calling on Franciscans throughout the world to sponsor creative projects to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the birth of St. Francis in 1982. Vitale – a friar who had a long history of peace and justice activism and at the time was the provincial of the Franciscan Friars’ St. Barbara province, a jurisdiction that included much of the western United States — thought that a project highlighting Franciscan peacemaking would be appropriate, especially at a moment when the newly-elected Reagan administration was vowing to modernize the U.S. military, including the three legs of its nuclear weapons system: sea-based submarines and ships, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, and its fleet of jet bombers. Not only did this renewed build-up seem to Vitale, a former U.S. air force pilot, likely to increase the danger of nuclear war, it would also lavish economic resources on weapons systems at a time when social programs would be slashed across the U.S.

At the time that he was mulling various possibilities, Vitale was approached by a recent graduate of the Franciscan School of Theology in Berkeley about the possibility of working for the St. Barbara province on peace issues. A former professor in Health Education at the State University of New York at Cortland who had decided to study theology in California, Michael Affleck had been actively organizing peace-related events in the San Francisco Bay Area since Daniel Berrigan had taught a course on nonviolence during the 1980-81 academic year at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Vitale was delighted with Affleck’s proposal and discussed his organizing a series of peace-oriented events for the province to mark St. Francis’ birthday the following year.

I said I would support this,” Vitale later recalled, “but only if one of the events took place at the Nevada Test Site.” Vitale, who had lived and ministered in Las Vegas for many years, had long been concerned about the U.S. government’s testing program at the test site. This was brought into sharp focus by a conversation that he had once had in the early 1970s with the editor of Commonweal, a progressive Catholic weekly magazine. At the time the activist community was still largely focused on ending the U.S war in Vietnam, but something the editor said caught Vitale’s attention. Even if they stopped the bloodshed in Indochina, Vitale remembers Jordan saying at the time, there are still tens of thousands of nuclear weapons aimed at the world’s children. This comment proved pivotal for this Franciscan priest who was motivated by his faith to work for a better world and who, at one time, had played a part in the nation’s strategic nuclear force structure. He had become curious about what the government was doing at the Nevada Test Site and was told by a friend with contacts within the U.S. Department of Energy that the test site had situation in a remote location, in part, to discourage protest. Vitale took this as a personal challenge.

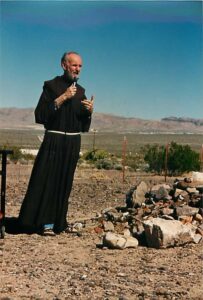

Affleck visited the test site. He later said, “I kept that trip very much in my heart and I began to think, Maybe we could have a vigil out there. Maybe this is what needs to happen. Maybe our response to the year of St. Francis would be to have a time in the desert where we are witnessing about this evil but we are going out in the real desert experience, not knowing what questions to ask, not knowing what direction we’re going to take, waiting, really, for the word of God to come to us, to give us some understanding of what has to happen next…. The whole thing began with the idea that we could pray and wait for some guidance on what to do, and that maybe out of this experience, out of the collective group understanding of those of us who went out there every day, we’d figure out what to do. But we didn’t know when we started…”

To conclude the 40 day vigil, 19 people—including Vitale, Bucher, Dan Ellsberg and others—were arrested as they crossed into the test site. “After being handcuffed, the nineteen were bussed sixty miles north to Beatty where they were jailed briefly and then presented before Nye County Justice Court Judge William Sullivan. The arrestees refused to pay the required $100 bail he imposed. The group desired to continue its vigil in jail through Easter. As Affleck recalls, “The judge ordered the protesters released but Louie Vitale, OFM…suggested that they would not leave. The judge said that if they did not leave they would be held in contempt of court and physically removed from jail. The judge voiced sympathy for ending nuclear testing.”

Louie Up Close

NDE participant Jane Hughes Gignoux reflected on her experience in an essay entitled “A Journey to Nevada,” quoted in Pilgrimage Through a Burning World:

Two white converted school buses pulled up in front of the community center in the tiny desert town of Beatty, Nevada. We were led, handcuffed, into a large, empty room and told to wait. It was then I saw Louie, still wearing his brown Franciscan habit. He came in through the door smiling easily and almost at once spotted a young man he apparently knew. Without hesitation he walked over to the young man and, in one huge sweeping gesture, lifted his arms, bound at the wrist, up and over the fellow’s head and then down, holding him in a warm embrace. It was such an easy, natural gesture, accompanied by words of welcome and comfort. “Wow!” I thought to myself, “That’s how I want to be – light-hearted, loving, compassionate.” It was true, of course, that Louie had been arrested many times over the years. Nevertheless, as I contrasted his performance with mine, I was aware of how much I had to learn about letting go and surrendering. When I saw how Louie radiated faith, hope, love from the center of his being, I resolved to keep at it until I could do the same.

Presently one of the marshals came and cut away our plastic handcuffs. Then I saw Louie in a corner of the room remove his brown robe, fold it reverently and, with this gesture, return to his chosen disguise as an ordinary man. In his plain black tee-shirt, cotton trousers, and sandals he could have been a truck driver, a salesman, a farmer, anyone at all. In fact, Louie Vitale is no ordinary man. He is the head of the Western Province of the Franciscan Friars with extensive responsibilities, and very much the spirit behind the protest and vigil movement at the Nevada Test Site. Except for brief moments, he prefers to remain in the background, allow others to coordinate the many complicated preparations that go into these protests. How exhilarating to be in the presence of a person who had no need to prove his power by attempting to control others. Here was someone who understood the source of his power and who obviously knew that no one could rob him of it. That, combined with his utter honesty and compassion, marked Louie as an example of a true leader. If such people were in government and business, how different a world it would be.

“Go with the Mystery”

NDE participant Patricia Roberts, reflected tenderly on her time in the desert in March, 1988 and the ineffable and inexplicable power of its continuing presence in her life:

Our group prepared here in New Jersey for the event yet there is no doubt that crossing the line was rather scary. The spiritual high point – and I’ll never forget it – was when a long and intimidating line of guards came towards us, demanded that we kneel and handcuffed us. I’d never been to the desert and to kneel there in its vastness, among blooming desert places – as one by one we sang peace songs – is a moment in my life for which words are not adequate. A feeling that all will be well. A freedom.

In December 1988 – nine months after I’d been to the desert – my husband of 33 years died, quite unexpectedly. For some strange reason, as devastating as this was, I feel that what I’d been part of at the desert softened his death. I wrote about this to Father Vitale; he replied saying, “Go with the mystery.” I am tearful thinking about this, but it is powerful and comforting to contemplate.”

Now, with Louie’s death, we hear his powerful words again: “Go with the mystery.”

Toby Blomé has sent out a list of “inspiring videos” with Louie speaking, or, in this case, about him:

What is Louis Vitale? Explain Louis Vitale, Define Louis Vitale, Meaning of Louis Vitale

Father Louis Vitale: Love Your Enemies – . Very inspiring talk that Includes overview of Peace Delegation to Iran in 2009, and many photos with Martha Hubert’s beautiful “Peace with Iran” banner. (58 min.)

Interfaith Service in Solidarity with Homeless People – Downtown Berkeley – 09 April 2015

Father Louis Vitale on Prop L: Unjust, Unwise…and downright silly. – 2010

Father Louis Vitale speaking at Occupy SF – 2011 (7 min.)

Interview with Father Louis Vitale – 2007. Truthout’s Executive Director Marc Ash interviews Father Vitale after his arrest at Fort Huachuca in Arizona protesting the training of interrogators in torture. (8.23 min.)

Dolores Huerta and Fr. Louis Vitale, In Conversation. https://youtu.be/0xMLW2Ob4Ts?si=JzB4WcX5Iza-TyW9.

Thank you, Toby!

from Pax Christi USA

Louis Vitale, Pax Christi USA Teacher of Peace, presente! 1932-2023

Pax Christi USA extends condolences to the friends and family of Fr. Louis Vitale, OFM, who died on September 6, 2023 at age 91.

Father Louie was a well-known and beloved Franciscan friar who embraced the call to nonviolent civil resistance as exemplified by Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., and was a fierce advocate for justice and care for homeless persons and others on the margins of society.

“My memories of Louie Vitale center on his joyful Franciscan spirit,” shared Joe Nangle, OFM, Pax Christi USA’s 2023 Teacher of Peace, and longtime friend of Fr. Louie. “Unlike the doomsday attitudes of some social activists, Louie always demonstrated that this serious work brings deep happiness. As his brother friar, I will forever be grateful for his wonderful Italian optimism – much like another Franciscan who even sang to the birds.”

Co-founder of Pace e Bene Nonviolence Service and the Nevada Desert Experience (which organizes public witnesses against nuclear testing), Father Louie shared the 2001 Pax Christi USA Teacher of Peace award with Phil Berrigan and Liz McAlister.

BAY AREA//SAN FRANCISCO

Father Louie Vitale, S.F. peace activist often arrested for the cause, dies at 91

Sam Whiting

Sep. 20, 2023 Updated: Sep. 20, 2023 5:23 p.m.

Father Louie Vitale greets a cab driver after sprinkling a taxi with holy water at the annual Blessing of the Taxicabs outside St. Boniface Church on Golden Gate Avenue in San Francisco in August 2005.

In his weekly homily, Father Louie Vitale could not contain himself when he looked out upon his flock of the poor and distraught at St. Boniface Catholic Church in the Tenderloin.

He’d smile and raise his hands and say, “It is just about love, all about love” to his audience, some of whom would be lying down in the pews asleep. These were his “brothers and sisters,” and he spoke to them in English at the 8 a.m. sermon, and in Spanish at 10 a.m.

If Vitale did not have his hands outstretched in a gesture of giving, they were usually behind his back being cuffed. True to his Franciscan spirituality, Vitale proved his love for all mankind by participating in acts of nonviolence and demonstrations for peace. He claimed to have been arrested some 400 times.

Most of his legal trouble came through his position as co-founder of the Nevada Desert Experience, which pressured the government to end nuclear weapons testing. Closer to home, he founded the Gubbio Project, which made St. Boniface the first church in America to let homeless men and women sleep in its pews during daytime.

That program continued long after he retired to the Mercy Retirement and Care Center in Oakland, where he died Sept. 6 after an all-night prayer vigil as he clutched his rosary beads. The cause of death was pneumonia, said his close friend and fellow activist Anne Symens-Bucher, who was with him until the end. He was 91.

“Louie was a dynamic and charismatic prophet for our times,” said the Rev. John Hardin of St. Boniface, which was established in 1864 as the first German language parish in San Francisco. A huge complex that houses a school, residences for the friary and a high-ceilinged church that seats 400, St. Boniface is across Golden Gate Avenue from St. Anthony’s Foundation, where parishioners often take their meals.

Father Louie Vitale opens the gates of St. Boniface Church in the Tenderloin before dawn in February 2005. St. Boniface was the first church in America to let homeless men and women sleep in its pews during daytime, and some typically waited outside for the church to open at 6 a.m.

“This is a sanctuary for the voiceless,” Hardin said, “and Father Louie became their spokesperson.”

The 100 block of Golden Gate Avenue is now closed to auto traffic, but before that, Vitale would stand in the street in his Franciscan habit for the annual Blessing of the Taxicabs, a drive-thru ceremony in which he would sprinkle holy water on car hoods and lean into windows to touch the drivers.

“Bless you, brother. Please drive safe,” he’d say. Or, “I pray God keeps you safe. You doing OK today?”

At age 84, in 2016, Vitale published “Love Is What Matters: Writings on Peace and Nonviolence,” detailing the life of what Chronicle reporter Kevin Fagan described as “one of the most — if not the most — rabble rousing peace activist priests in Northern California.”

Vitale had the credentials to back that statement. In 1982, he and Symens-Bucher created the Nevada Desert Experience to bring protesters out to the Mojave Desert near Las Vegas, and bring awareness to a federal weapons test site. They helped get the testing stopped, but it took years and years of persistent witness, including the 40-day season of Lent.

Vitale would stand by the road in his habit, tall and thin, always holding a sign calling for disarmament. Hours of this, in heat or cold and wind, were followed by a homily he’d deliver to as many as 100 protesters in a circle. Among those standing and listening was Martin Sheen, the actor and activist. “Father Louie is the best follower of St. Francis of Assisi that I know,” Sheen later wrote.

Another witness was Sally Hindman, a Berkeley advocate for the unhoused and Quaker minister involved in civil disobedience.

“Louie Vitale lived his Franciscan values at the deepest level,” she said, “and put his faith into action in profound ways by putting his body on the line over and over again, as needed in order to live out his Christian faith.”

Louis Vitale was born June 1, 1932, in San Gabriel (Los Angeles County) and raised in Pasadena, where his father was a seafood distributor. Vitale attended a military academy and joined the ROTC at Loyola University in Los Angeles. Upon graduation in the early 1950s, he was commissioned a lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force.

He was a navigator and bombardier, and in one instance his plane targeted what was detected to be a Soviet military aircraft headed over the North Pole. Vitale was preparing to fire a missile when the target plane was determined to be carrying civilians. That near miss turned his head around, and he soon left the military for the ministry.

When he arrived at St. Boniface in 1992, it was to fill an interim position for nine months, which turned into 13 years. He lived in a monk’s cell below the church tower.

Known for fasting, he kept getting thinner, which only accentuated his ears, which were huge to begin with. “The better to hear you with,” Vitale would say.

One thing he heard was the Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989, which damaged St. Boniface. Vitale oversaw a retrofitting project after raising $13 million to get it done.

While working on that project, Vitale co-founded Pace e Bene (Peace and All Good), an action organization that trained 40,000 people worldwide in how to carry out nonviolent strategies for change. Its annual mobilization is Sept. 21, to involve some 5,000 actions.

“Louie lived by a simple equation,” said Ken Butigan, a professor of peace studies at DePaul University in Chicago. “Love plus clarity plus determination plus hundreds of arrests leads to a life well-lived for the well-being of all.”

Aug. 31, 2005, was his final day at St. Boniface, the annual Blessing of the Taxicabs.

Father Louie Vitale of St. Boniface Church in the Tenderloin is assisted by Nicholas Hernandez at the annual Blessing of the Taxicabs on Golden Gate Avenue in San Francisco in August 2003.

“This isn’t the end of my work for God,” he said afterward. “You’ll probably see me again, maybe getting arrested somewhere.”

He was true to his word. Within six months he had been arrested at the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation in Fort Benning, Ga., for protesting the teaching of interrogation techniques.

When he got arrested for a second time at Fort Benning, he earned himself six months in federal prison, first in Georgia, then in Lompoc in Santa Barbara County. He got a job cleaning the prison chapel and had no complaints about the accommodations or the company.

“I’m getting to know a lot of guys here, and they’re very receptive,” he told the Chronicle’s Fagan in a collect phone call — the way they always communicated. “A lot of guys want to talk.”

In 2011, when Vitale was 79 and had been released from one of his longer sentences, his return to San Francisco was celebrated by Pace e Bene with a mass at the National Shrine of Francis of Assisi monument in North Beach. More than 100 people came, with speeches delivered by Daniel Ellsberg and Laura Slattery of the Gubbio Project, which has since moved to St. John the Evangelist in the Mission District.

St. Boniface still offers Sacred Sleep, a project run by the St. Anthony Foundation. The people who pass their days in the church and everybody else can give thanks to Vitale at a Memorial Mass at 3 p.m. Oct. 6 at St. Boniface.

“The greatest tribute that we can give to Father Louie is to follow his example as peacemakers in a world that is headed toward destruction,” said Hardin, who will be master of ceremonies at the event. “He saw all of humanity and Mother Earth herself as divinely created and dedicated his life to peace and justice.”

Written by Sam Whiting

Sam Whiting has been a staff writer at The San Francisco Chronicle since 1988. He started as a feature writer in the People section, which was anchored by Herb Caen’s column, and has written about people ever since. He is a general assignment reporter with a focus on writing feature-length obituaries. He lives in San Francisco and walks three miles a day on the steep city streets.

xxx

Fr. Louie Vitale, ofm Presente!

by Dennis Apel

I went to Louie’s funeral last Saturday [September 23]. Mission San Luis Rey near Oceanside, California was as beautiful as I remembered it from the days decades ago when I was a seminarian there studying philosophy. The church was long and narrow, somewhat dimly lit, with candelabras hanging from a high ceiling, sunlight streaming through the deep-set windows in the 5-foot-thick adobe walls intricately hand-painted on the inside in dusty muted colors, hard wooden pews and kneelers on a red stone floor, a stark and lifelike crucifix with a battered and bleeding Jesus hanging behind the wooden altar.

There were maybe a hundred or so in attendance, about half of them friars in brown habits, many of them as old or older than Louie. Like Louie they have given their lives to the traditional Franciscan rule of poverty, chastity and obedience. But Louie also gave his life to a radical and unwavering activism that not many have emulated. He was arrested perhaps over 400 times for acts of civil disobedience and spent considerable months of his life incarcerated and ministering to fellow inmates. He was interested in moral causes from the abolition of nuclear

weapons to the abolition of torture to the abolition of homelessness. He was keenly focused and contagiously happy and he exuded kindness and compassion. To be known by him was to be loved by him, and he was deeply loved in return.

As I sat in the church I couldn’t help but reflect on Louie’s life and example and the effectiveness of his activism. After all, for all his passion to rid the world of nuclear weapons, torture, homelessness, etc., all of them are still with us and really show no overt signs of going away. A cynical person might look at his life and say, “What a fool. He lived all that for nothing.” But anyone focused on the lessons of the gospels would recog- nize that efficacy was never the point, faithfulness was. And Louie was nothing if not faithful.

I remember the first time I met Louie. It was the mid 1960’s and I was a high school seminarian at St. Anthony’s in Santa Barbara back when I thought I was going to be a Franciscan. One day an old badly-beat-up station wagon rolled into the parking lot and out stepped a very humble looking Mexican family. The driver who also seemed to me to be the husband/father was short and slender and moving slowly. He didn’t look well. That evening, as the 200 or so of us seminarians sat in the refectory waiting for dinner to be served, Fr, Louie Vitale walked in with the man from the station wagon. Louie introduced himself to all of us and then he introduced Cesar Chavez who had come to the seminary for respite and renewal after completing a month-long fast for the cause of human rights and dignity for field workers. Cesar Chavez addressed us all and when he finished Louie threw his fist in the air and with a huge grin and disarming energy belted out, “Right on!!” Right on? I had never heard the phrase, nor did I understand it. But I was instantly caught up with the energy of it and with Louie’s energy as well. As our paths crossed over the ensuing years, I never forgot that initial image of Louie and his energy, even as it waned in his later years, but it never gave way to a loss of his contagious spirit. When you were with Louie you were in the presence of something holy.

As life goes we didn’t have much interaction in the years after that, just an occasional crossing of paths. Louie worked in Las Vegas near the Nevada Test site resisting the testing of nuclear weapons. From there he became a pastor in San Francisco where, despite the disdain of some retractors, he let the homeless sleep in the safety of the pews of his church. Eventually he became the provincial of his order.

One of the happiest and most grateful days of my life was the day that I was arrested at Vandenberg Air Force Base for an act of civil disobedience with both Fr. Louie Vitale, ofm and Fr. Steve Kelly, sj. Both of them were long-time heroes of mine and both of them had rich histories of speaking truth to power and accepting the consequences. It was the anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and as Louie, a retired Air Force bombardier, was want to point out, the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki was dropped by Catholic men on a city that had the highest population of Catholics in Japan. How could that anniversary pass without some public comment on our nuclear program and its assertion that it’s okay to deploy weapons that will indiscriminately incinerate hundreds of thousands of civilians regardless of their religion, their politics, their ideologies, their age, their loyalties or their participation in their government’s actions. I was in good company that day!

And I was in good company as I knelt on the hard wood kneeler at Mission San Luis Rey having shared communion with a humble group of people who had been touched by Louie’s life and example and had gathered to support his family and each other in their grief over the loss of a rare and beautiful spirit. Memories and reflections wafted through my mind and I was immersed in the mystery of life and our decisions and our understanding of the gospels and the people we see as mentors. And even in the mystery of it all, I was grateful for the questions. That in itself is a blessing.

As I sat on the hard pew and fixed my gaze on the image of Jesus on the crucifix behind the altar I realized that, like Jesus, Louie’s life, although seemingly ineffective from the perspective of the world, was a blueprint for living morally in an immoral world. Kindness, compassion, inclusivity, and a selfless regard for the unseen or unwanted were the code that he lived by, not so much to change the world but to be God’s unconditional love in the darkness of the world as it is. The point is not to live as if we can change the world but to live as if the world, as it is, cannot extinguish our light with its darkness. May he, and eventually we, rest in Jesus’ peace. Right on!!

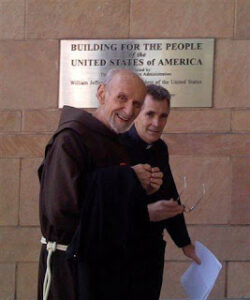

October 2007 – Fr. Louis Vitale, O.F.M. and Fr. Steve Kelly, S.J., on their way into the U.S. federal courthouse in Tucson, AZ (where they were sentenced to 5 months for torture protest at Ft. Huachuca, AZ) (photo by Lee Stanley)